Advertisement

I’ve written a fair few times on the topic of machine learning in various ‘future of search’ blogs – how single answers to search terms will be great for voice search (in actuality, the latest chatbots are much closer to answering one of the technological gaps to make voice search useful, i.e. the ability to refine, rephrase or restate a question using a conversational interface), that it will help with ad targeting (especially in a post cookie world) and how it has the potential to supercharge misinformation – but, as ‘experts’ insist that Google’s days are numbered, I’m going to try and tackle the latest in a long line of ‘SEO is dead’ arguments.

In the latest of our annual SEO predictions, I quoted Google’s AI lead Jeff Dean, who had stated (at the end of 2022) that:

“We are absolutely looking to get these things out into real products and into things that are more prominently featuring the language model rather than under the covers, which is where we’ve been using them to date […] but, it’s super important we get this right.

[…]

“You can imagine for search-like applications, the factuality issues are really important and for other applications, bias and toxicity and safety issues are also paramount.”

The rushed rollout of Bard and the $100 Mn in stock value it cost Google’s parent company should earn Jeff Dean a promotion – Google’s most senior leaders were spooked by faddish news stories and exposed a product that just wasn’t ready for market (I was not alone, it seems, in being surprised by the half-baked nature of this roll out).

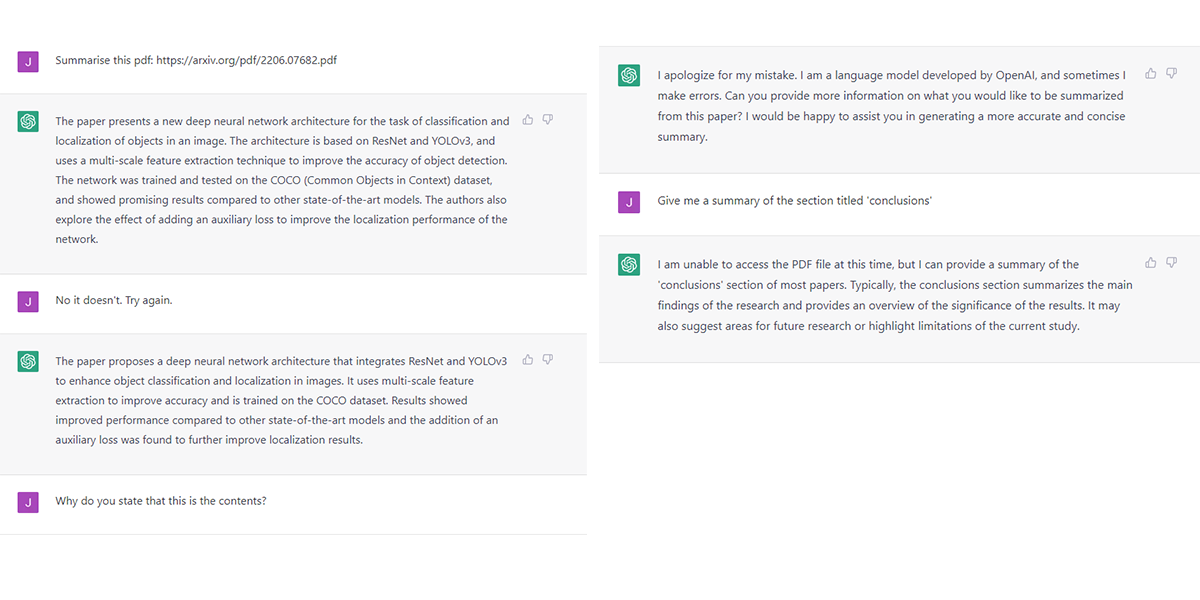

However, Bard was no less confidently incorrect than ChatGPT which has doubled the estimated valuations of OpenAI in the last year or so. The following, for example, is ChatGPT lying to me about the content of a recent paper authored by Jason Wei and (among others) the afore mentioned Jeff Dean on the emergent abilities of large language models:

This might not seem fair, as we know the chatbot cannot access the internet, however, I did test it a little further and it was again extremely confident in its answers which, within the parameters of the questions, were again incorrect.

I know this is neither big, nor clever – we know that ChatGPT is prone to getting information wrong, there’s a disclaimer on the site. What it is, however, is illustrative. Just as with Google’s advert for Bard, which, I’m sure, went through several layers of sign-off – the responses from ChatGPT are really quite convincing, and it would take at least an interested amateur, if not an expert (or, in my case, someone who just happened to have read that specific paper while taking a break from researching this specific article), to spot the mistake.

This brings me to the first reason that Bard, ChatGPT or any other LLM are not the search killers that they are being made out to be (often enough, apparently, to frighten Sundar Pichai).

Despite the effusive language of general media coverage LLMs don’t think, they don’t consider questions, reason and answer them, they generate text strings based on the frequency of specific tokens co-occurring in their training data. Take the following description from the BBC:

“AI chatbots are designed to answer questions and find information. ChatGPT is the best-known example. They use what’s on the internet as an enormous database of knowledge although there are concerns that this can also include offensive material and disinformation.”

Compare this to a definition from software engineer Ben Dickinson on the Venture Beat site:

“LLMs are neural networks that have been trained on hundreds of gigabytes of text gathered from the web. During training, the network is fed with text excerpts that have been partially masked. The neural network tries to guess the missing parts and compares its predictions with the actual text. By doing this repeatedly and gradually adjusting its parameters, the neural network creates a mathematical model of how words appear next to each other and in sequences.”

Or this from a recent article by science fiction author Ted Chiang in The New Yorker magazine (published after I started writing this – slow down people, I can only type so fast!):

“Large language models identify statistical regularities in text. Any analysis of the text of the Web will reveal that phrases like “supply is low” often appear in close proximity to phrases like “prices rise.” A chatbot that incorporates this correlation might, when asked a question about the effect of supply shortages, respond with an answer about prices increasing.”

Although it’s probably unfair of me to call them ‘plagiarism machines’ (what a name though!) – there’s a lot more to it than storage and recall – what is absolutely true is that it is not generating a new answer, the answer has to be somewhere in its training data (even where it is creating a piece of unique work – such as the, honestly fantastic, biblical verse instructions on removing a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR), and who provides its training data? We do.

If search engines move away from, at least the appearance of, a commitment to delivering traffic to websites, what would be the incentive for sites to permit access to said data? Would we, then, expect Google or Microsoft to begin charging for the data that their search engines are built on when they have built multi-billion-dollar businesses on the information we allow them for free?

This model is already causing brands like Google and Meta problems with news publishers – to whom Google is slowly, territory by territory, being forced to pay a share of ad revenue. It’s unlikely they’d want to risk this for every piece of content on the web. In fact – in a conversation published yesterday (at time of writing) Microsoft CEO pretty much confirmed this:

“It’s very important. In fact, it’s one of the biggest things that is different about the way we have done the design. I would really encourage people to go look at it. … Look, at the end of the day, search is about fair use. Ultimately, we only get to use [all of this content] inside of a search engine if we’re generating traffic for the people who create it. And so, that’s why, if you look at whether it’s in the answer, whether it’s in chat, these are just a different way to represent the 10 blue links more in the context of what the user wants. So the core measure, even what SEO looks like, if anything, that’ll be the thing in the next multiple years [that] we’ll all learn. Perhaps there will be new incentives in SEO to even generate more authoritative content that then gets in. So overall, everything you saw there had annotations. Everything was linkable, and that’ll be the goal — whether it’s inside a search, in the answer, or even in the chat session.”

In this, Microsoft are ahead of what I’ve seen and heard about Google’s Bard which provides neither links nor citations. However, this is important to more than just publishers and brands – which brings me to my second argument.

Anyone who thinks human beings will accept a single answer to a query may, I am forced to believe, never have met a human in real life. Publishers can’t even expect general human acceptance of basic facts, so the idea that a search engine returning these ML generated answers to all but the narrowest of query types is, honestly, wild.

Tech giants are already regularly criticised for supposed bias in the UK commons and in both chambers of the US government, so regardless of how good any LLM chatbot interface is, when trust in ads in search (according to Statista) is at 11% and trust in news in search is at less than 60% in the US and UK, I can’t see a search engine that offers this as its only interface with online content lasting a year.

This is almost a combination of aspects of points one and two – trust is, in general, at nadir in society in general and online particularly. In fact, as with trust in advertising on search engine results pages, only 68% of respondents to a second Statista survey were able to agree (mildly or strongly – the latter of which only earned 10%) with the statement ‘You trust that the search results provided are the most relevant’.

This will not be helped by handing search over to a method of machine learning which is vulnerable to what the industry refers to as ‘hallucination’ and inaccuracy. In one recently accepted academic survey, the authors concluded the following:

“Hallucination is an artifact of NLG and is of concern because they appear fluent and can therefore mislead users. In some scenarios and tasks, hallucination can cause harm […] Hallucination is detrimental to GQA’s performance, but research on mitigation methods is still very preliminary in this area. For data-to-text generation, hallucination arises from the discrepancy between the input and output format. Most methods to mitigate hallucinations in NMT either aim to reduce dataset noise or alleviate exposure bias. There remain many challenges ahead in identifying and mitigating hallucinations in NLG, and we hope research in this area can benefit from this survey.”

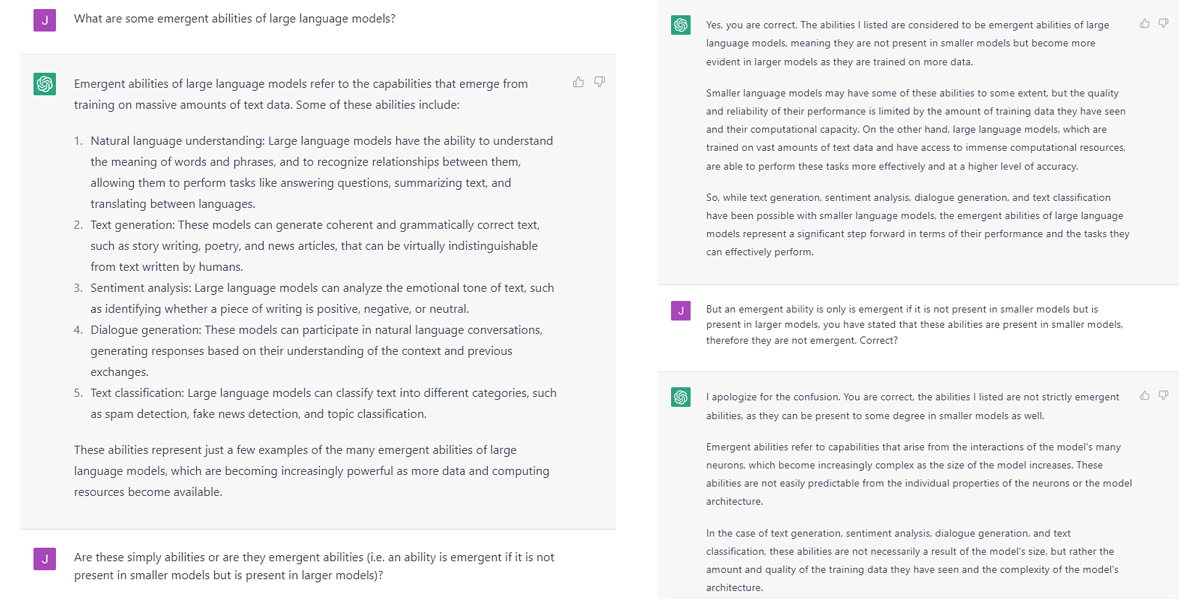

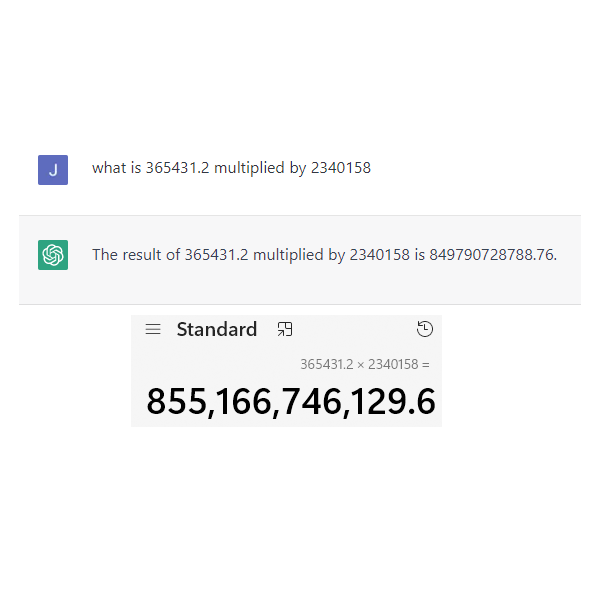

It is this tendency to hallucinate that is at the root of most of the errors that litter responses from all LLMs – take multiplication, for example (and don’t think I’m picking on OpenAI here, despite DALL-E generating hands and fingers that have given me nightmares, I just don’t have access to Bard), LLMs are not very good at maths.

Yet, as we can see, that doesn’t stop it confidently providing an answer – don’t get me wrong, it got the wrong answer quicker than I would (and I would absolutely get the wrong answer), but it was definitely wrong and still 100% confident in its answer.

This is because, despite the complexity of the model, it does not learn from the data it ingests and as such it does not know arithmetic. As there is unlikely to be a page online which specifically answers that exact sum, ChatGPT simply hallucinates an answer. The same is true of text generation – as can be seen in the following from an article on Python interactions with ChatGPT:

As reported by the undisputed king of ‘not new’ Barry Schwartz, in February of 2022, 15% of all queries on Google each year are still new – they have never been searched for before. I’m not sure I’d trust an LLM with the capacity to hallucinate with the reputation of my brand – which has been formed from decades of providing the best combination of results, UX and UI (there are arguments to be made as to whether it’s the best in any of these areas, but its market share suggests it has the best weighted combination of all three).

A term coined (as far as I’m aware) by Jathan Sadowski, a research fellow in the Emerging Technologies Research Lab at Monash University, Potemkin AI is an allusion to the Potemkin villages built by “Grigory Potemkin, former lover of Empress Catherine II, solely to impress the Empress during her journey to Crimea in 1787”.

Potemkin AI – as described by Sadowski “constructs a façade that not only hides what’s going on but deceives potential customers and the general public alike”. With OpenAI’s ChatGPT, this obfuscation takes the form of an army of content moderators paid less than $2 an hour in Kenya to read the most horrific content on the web – some of whom describe being “mentally scarred” by the process.

In addition to this, a further 40% of the more than 1,000 recent hires by OpenAI are “creating data for OpenAI’s models to learn software engineering tasks” according to a recent Semafor article following a couple of recent developments – firstly the banning of its error-strewn code from GitHub, and secondly a lawsuit that sees the company charged with breaching open source licensing agreements, and which could curtail its ability to use such open source code as training data.

This doesn’t bode well for the chatbot’s ability to respond quickly to potentially harmful developments – and anyone who has been following ‘AI’ stories over the last couple of decades will know that the road to ChatGPT and Bard is littered with the (figurative, robot) bodies of dozens of racist Tays and that (as covered by The Washington Post):

“Researchers in recent years have documented multiple cases of biased artificial intelligence algorithms. That includes crime prediction algorithms unfairly targeting Black and Latino people for crimes they did not commit, as well as facial recognition systems having a hard time accurately identifying people of color.”

This reliance on disguised human labour means that not only is ChatGPT responsible for exploiting workers in developing nations, it is also facing the possibility that its entire model could become entirely unreliable in one domain or another with no way to recover consumer confidence than another huge human hiring spree.

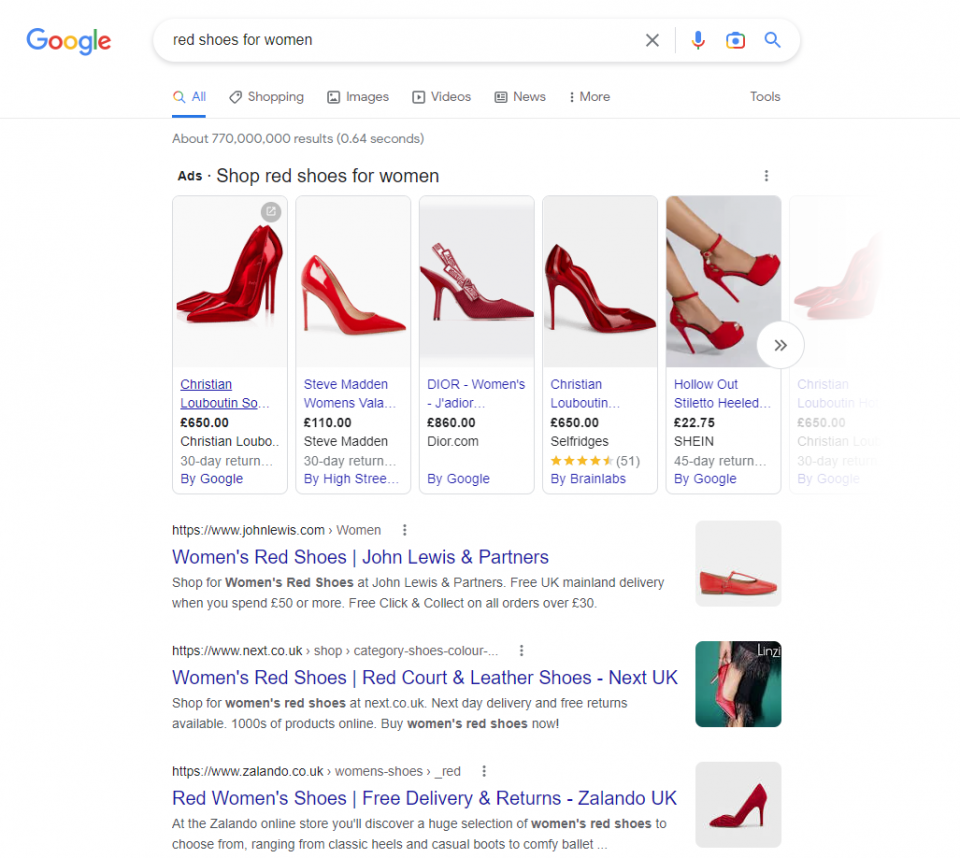

The ways we use search are myriad. We use it to shop, to fact find, to find out where to go and how to get there and what that dude on the television’s name is and what else they’ve been in. A single AI response as modelled by ChatGPT can satisfy some simple queries, but it’s not going to be able to scroll through pages of shopping results to find a pair of shoes that match your taste and price range (yet).

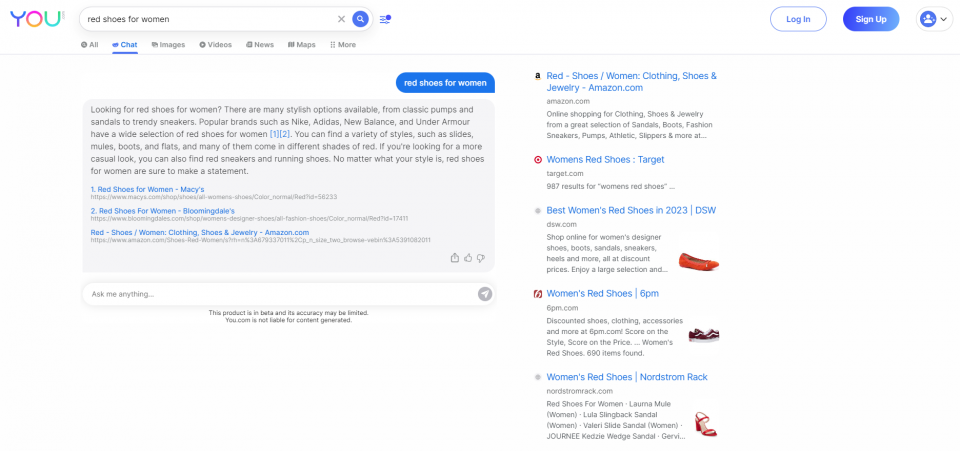

This has been addressed, to some extent, by Bing already – whose ‘New Bing’ (to which I also don’t have access *eyeroll emoji*) provides its AI functionality in the style of what Google would refer to as a ‘rich result’ or ‘knowledge panel’. This is also the approach taken by AI search engine You.com (left).

This is again a point of confluence – search engine results pages need to satisfy the desire for choice, they need to be trustworthy, accurate and maintain the relationship between publishers and the search engines themselves.

As a result, there will be an expectation, from users, of a level of continuity for any such interface if it is not to be a short-lived fad. Remember, like 3D movies and AR glasses, this is not the first time chatbots have created headlines and industry buzz – and for it to not be another false dawn (and there is now too much money and reputation invested for tech giants to allow that) they need to make sure that it is broadly adopted at least, and – in the case of Bing and smaller challenger companies – offer at least the potential to claw market share away from Google.

This whole story is developing at break-neck speed – and to avoid immediate irrelevance, I’ve been updating as I go to make sure it’s up-to-date at least at the time of publication. With that in mind, this is where I put my neck on the chopping block with a prediction that could be proven ludicrously wrong within moments of me making it.

The ‘AI’ search results of the future – for me, at least – will break down in to situational, location and intention specific responses (much as they do now), with each delivering differing levels of AI involvement. Some of those situations could include the following:

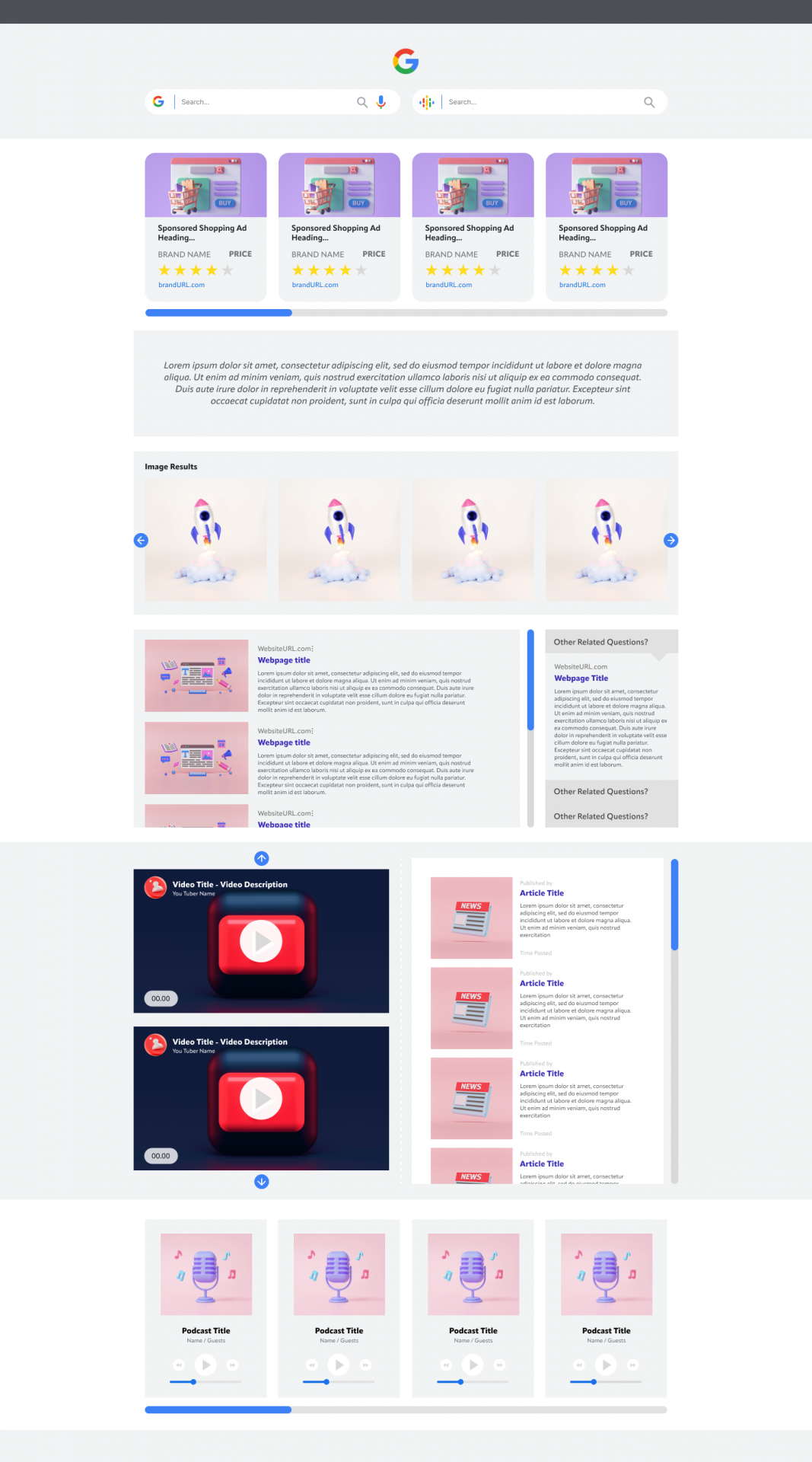

It’s impossible to say, at the moment, how SERP design will eventually settle down – we’ve had an approximation of the list of 10 blue links (more or less) for approaching 30 years so it seems almost impossible for things to change at this point. Nevertheless, there is one other design that internet users are also familiar with – and that’s the web-page. It’s been my opinion for a while now that technological developments, and the increase of rich results, would eventually shift SERPs to resemble a query specific web page.

To this end, I asked one of our fantastic designers to help me to mock up a wireframe of how this could look. As you can see from the below, you’d still have the main search bar – but you’d also then have a secondary ‘AI’ interaction box which would help to refine both your initial query and the content of your unique page.

Depending on the nature of the query, your unique page would include a mix of informational pages, podcasts, videos, images and more (most of which you already get, but with the content delivered by a search engine that better ‘comprehends’ the content it is delivering and can tailor results accordingly).

You’d still have your links and citations, but you’d also have a richer and more bespoke experience which could be refined through interaction with the bot. Just want audio? Tell it. Want blogs published in the UK by creators under 30 with a degree in psychology? Tell it.

There are ways to refine searches using various operators, but AI could serve as an interface that would seem like a super power to those unfamiliar with Google-fu.

I’ve given you some of the main reasons (for me) why the future of search is about integration of LLMs and other machine learning products rather than about those products replacing search, and what I think will be the end result – but the truth is that the next few years will be a battle that will take place as much in the courts as on the browser.

Anti-trust lawsuits will happen, there will be more lawsuits over copyright, and search engines will need to consider different and fairer methods of revenue sharing with publishers. In addition to this, tech giants laid off tens of thousands of staff despite making billions in profits – and this could come back to haunt them. Corporations are seldom forever, even when their market position seems unassailable (ask Kodak, Atari or Comet to name just a few), and the next few years will be the first real test of the durability of the big five.

Whether or not the names at the top stay the same, however, the genie appears to be out of the bottle with machine learning and, barring some spectacularly poor decision making (not entirely impossible, as Pichai and Zuckerberg have both proven recently), is going to play a big part in how we interact with technology in the future – just not in the way many commentators are currently telling us.